A Unified Theory of Temporal Dynamics

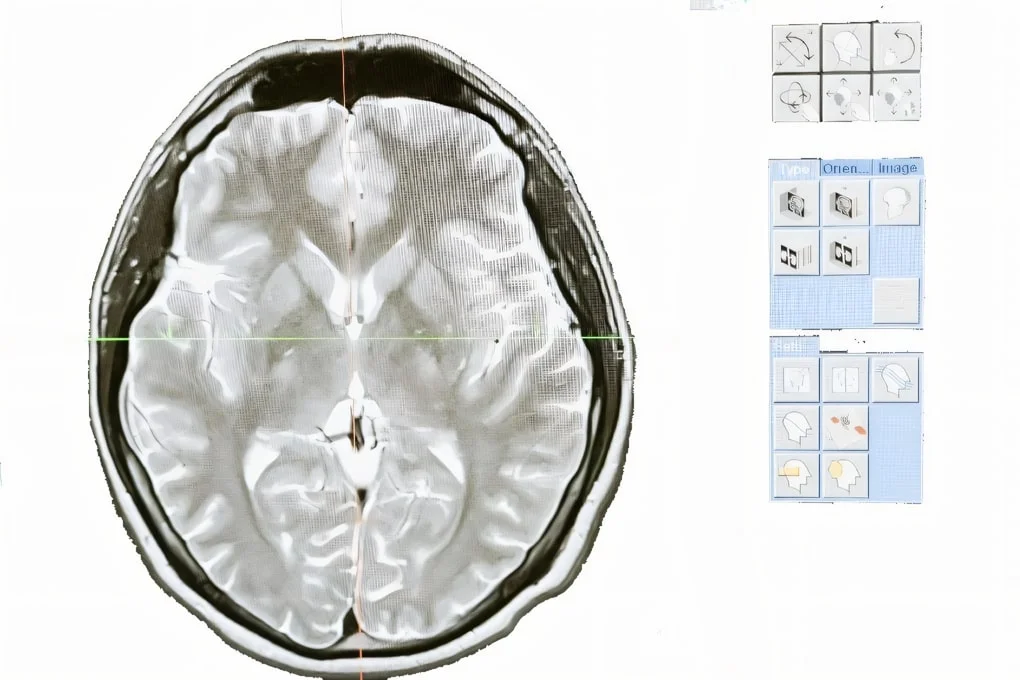

The "clock" in our heads is, in reality, a symphony of neurochemical interactions. As we have seen throughout this series, the perception of time is constructed from the synchronized activity of distributed neural circuits, primarily involving the striatum, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. The key to this construction lies in the delicate balance between two opposing yet complementary neuromodulatory systems: Dopamine (DA) and Serotonin (5-HT).

Dopamine, acting through striatal D2 receptors, sets the tempo of the Striatal Beat Frequency mechanism. It drives the "speed" of the clock and, through D1 receptors, fuels the motivation to engage in timing behavior. It stamps in the memory of "when" a reward occurs. Serotonin, conversely, acts as the regulator of patience. Through 5-HT1A receptors in the hippocampus and 5-HT2C receptors in the basal ganglia, it can slow the subjective passage of time, extend the integration window of "time cells," and facilitate the waiting required for delayed gratification. Together, they allow an organism to navigate a temporally complex world—speeding up to seize opportunities and slowing down to endure necessary delays.

Future Directions: Precision Medicine for the Mind

This integrated understanding paves the way for novel therapeutic interventions. If a patient with Schizophrenia suffers from a "fragmented" timeline due to cortical desynchronization, could transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) tuned to specific theta frequencies re-bind their temporal experience? If an autistic child struggles with the rapid temporal dynamics of speech, could targeted modulation of specific striatal circuits via highly selective D1 agonists (or future gene therapies) increase the resolution of their internal clock?

The future of temporal neuroscience lies in moving from general "clock" metaphors to specific, circuit-based interventions. By targeting the precise receptor subtypes (e.g., specific 5-HT2C allosteric modulators) and the specific oscillatory bands involved in localized timing circuits, we may one day be able to "tune" the internal clock with the precision of a master watchmaker, alleviating the profound burden of temporal dysregulation in neuropsychiatric disease.

References

- Allman, M. J., & Meck, W. H. (2012). Pathophysiological distortions in time perception and timed performance. Brain, 135(3), 656-677.

- Coull, J. T., Cheng, R. K., & Meck, W. H. (2011). Neuroanatomical and neurochemical substrates of timing. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36(1), 3-25.

- Eichenbaum, H. (2014). Time cells in the hippocampus: a new dimension for mapping memories. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(11), 732-744.

- Matell, M. S., & Meck, W. H. (2004). Cortico-striatal circuits and interval timing: coincidence detection of oscillatory processes. Cognitive Brain Research, 21(2), 139-170.

- Meck, W. H. (1996). Neuropharmacology of timing and time perception. Cognitive Brain Research, 3(3-4), 227-242.

- Paton, J. J., & Buonomano, D. V. (2018). The neural basis of timing: Distributed mechanisms for diverse functions. Neuron, 98(4), 687-705.

- Soares, S., Atallah, B. V., & Paton, J. J. (2016). Midbrain dopamine neurons control judgment of time. Science, 354(6317), 1273-1277.

- Wittmann, M. (2009). The inner experience of time. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1525), 1955-1967.

Excerpt from: Unveiling Temporal Dynamics Probing Serotonin and Dopamine Effects on Time Cell Function Through Integrated Approaches by Peter De Ceuster

© All rights reserved. Do not distribute.